Manned Flight Attempts

Despite resolving to conclude his experiments in aerodromics in 1896, Samuel Pierpont Langley’s desire to achieve human flight became irresistible. After all, Langley had devoted the prior decade of his life to bringing mechanical flight to reality; who better to take this singular, final step? With the Smithsonian Institute’s resources behind him, he constructed 1/4 scale models of a machine he believed would soon carry a man into the sky.

Langley’s work was buoyed by a new patron, President William McKinley, who, as Langley had foreseen, sought to exploit the aerodrome as a weapon of war. In 1898, Langley received a request from the Board of Ordnance and Fortification to construct a man-carrying aerodrome. Langley responded to the Board in a letter dated December 12, 1898,

“Gentlemen: In response to your invitation, I repeat what I had the honor to say to the Board—that I am willing, with the consent of the Regents of this Institution, to undertake for the Government the further investigation of the subject of the construction of a flying machine on a scale capable of carrying a man, the investigation to include the construction, development and test of such a machine under conditions left as far as practicable in my discretion, it being understood that my services are given to the Government in such time as may not be occupied by the business of the Institution, and without charge.

I have reason to believe that the cost of the construction will come within the sum of $50,000.00, and that not more than one-half of that will be called for in the coming year. I entirely agree with what I understand to be the wish of the Board that privacy be observed with regard to the work, and only when it reaches a successful completion shall I wish to make public the fact of its success.”

“Langley with his Aerodrome, Smithsonian Institution Archives, Record Unit 95, Box 15, Folder: 9A, https://ids.si.edu/ids/deliveryService?id=SIA-82-3207

Langley & Manly, 1903.

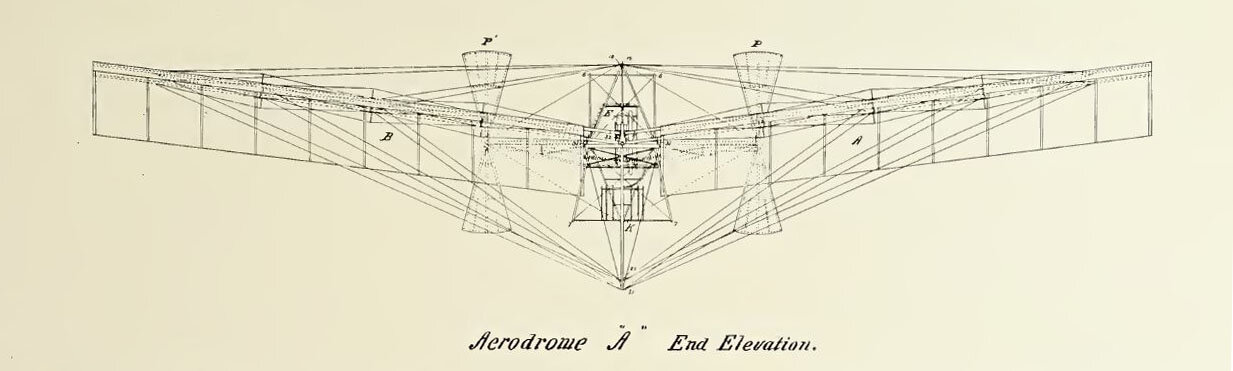

Brimming with confidence in his research, Langley set out to scale up his successful 1896 aerodrome models (the “Langley-type”), rather than considering alternative designs. While the Langley-type airframe was a practical solution for a 24 lb model, it posed massive structural challenges when scaled up to a man-carrying aerodrome weighing over 600 lbs. What Langley did have going for him was his engine. When the New York engine maker Langley contracted to build the aerodrome’s engine failed to deliver, Langley’s chief assistant, Charles Manly designed a revolutionary rotary-cylinder, internal combustion engine which produced 52 horsepower at a weight of just 124 lbs. Langley’s team also retrofitted the houseboat launching apparatus which, due to the increased weight, would launch the aerodrome from below rather than from above the aircraft. Following successful tests of a quarter-size aerodrome model in August, Langley’s Great Aerodrome ‘A’ was finally ready for flight on October 7, 1903.

Seated in the “aviator’s car,” a tight enclosed space between the engine and the front bearing plates, Manly gave the order to release the aerodrome. Upon reaching the end of the rails Manly described the force of a great shock followed by a plunge directly into the waters of the Potomac. He barely escaped with his life. A reporter described the flight as follows, “ A mechanic stooped, cut the cable holding the catapult; there was a roaring, grinding noise--and the Langley airship tumbled over the edge of the houseboat and disappeared in the river, sixteen feet below. It simply slid into the water like a handful of mortar..."

Aerodrome A Wreckage, October 7, 1903

Under intense criticism for the failure despite the massive public investment in his project, Langley went on damage control. A conflict between the front guy-post and its guide block on the launching car was blamed for the failure, otherwise, Langley postulated, the aerodrome and Manly, would have surely flown. To the press, Langley drafted a letter urging patience and discretion:

“The present experiments being made in mechanical flight have been carried on partly with funds provided by the Board of Ordnance and Fortification and partly from private sources, and from a special endowment of the Smithsonian Institution. The experiments are carried on with the approval of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution. The public's interest in them may lead to an unfounded expectation as to their immediate results, without an explanation which is here briefly given.

These trials, with some already conducted with steam-driven flying machines, are believed to be the first in the history of invention where bodies, far heavier than the air itself, have been sustained in the air for more than a few seconds by purely mechanical means. In my previous trials, success has only been reached after initial failures, which alone have taught the way to it, and I know no reason why the prospective trials should be an exception. It is possible, rather than probable, that it may be otherwise now, but judging them from the light of past experience, it is to be regretted that the enforced publicity which has been given to these initial experiments, which are essentially experiments and nothing else, may lead to quite unfounded expectations. It is the practice of all scientific men, indeed of all prudent men, not to make public the results of their work till these are certain. This consideration, and not any desire to withhold from the public matters in which the public is interested, has dictated the policy thus far pursued here.

The fullest publicity, consistent with the national interest (since these recent experiments have for their object the development of a machine for war purposes), will be given to this work when it reaches a stage which warrants publication.”

After extensive repairs were completed, a redemptive flight of Aerodrome A on December 8th ended with an even more disastrous result. The tail of the aerodrome caught on the launching mechanism, nearly shearing the craft in two. Nine days later, on December 17, 1903, Wilbur and Orville Wright would become the first to achieve powered human flight in Kitty Hawk, North Carolina.

The failure of his Great Aerodrome, despite the massive expenditure of public funds in support of the effort, led to public ridicule and embarrassment for the prideful Langley. His humiliation continued in 1905 upon the discovery that the Smithsonian’s accountant was embezzling funds under his watch. Shortly thereafter Langley suffered a stroke and died on February 27, 1906 at the age of 71.

After his death, the Smithsonian Board of Regents declared Langley as the first to construct a machine capable of achieving human flight. The declaration was likely driven by multiple interests, including the resurrection of Langley’s and the Smithsonian’s reputation, justification the public expenditures on the aerodrome, and to stake a public claim to the lucrative patent rights to the airplane. The Smithsonian would go as far as to contract Glenn Curtiss to pilot a visually similar yet structurally and mechanically enhanced Aerodrome A in 1914 to prove their case. These attempts would lead to a public relations debacle for all parties involved and the display of the Wright Flyer in London instead of the United States in 1928. In 1942, the Smithsonian retracted its claims and officially credited the 1903 Flyer as the “first powered, heavier-than-air machine to achieve controlled, sustained flight with a pilot aboard.”

In 1943, the Flyer was sold to the Smithsonian under the condition that, “Neither the Smithsonian Institution or its successors, nor any museum or other agency, bureau or facilities administered for the United States of America by the Smithsonian Institution or its successors shall publish or permit to be displayed a statement or label in connection with or in respect of any aircraft model or design of earlier date than the Wright Aeroplane of 1903, claiming in effect that such aircraft was capable of carrying a man under its own power in controlled flight.”

Langley’s Legacy

The failure of his 1903 manned flight attempts would unfortunately tarnish Langley’s reputation and overshadow his seminal achievement of heavier-than-air mechanical flight in 1896. Langley’s work brought respectability and credibility to what was once considered quackery, the science of aerodynamics and aeronautics, and paved the way for generations of inventors, engineers, and scientists who contributed to man’s conquest of the skies.

In December, 1906, fellow aviation pioneer Octave Chanute wrote, “He rescued the problem from contempt, he laid the lines which must be followed, and, having published the results of his experiments and given other men data upon which to conquer the air, he will ever be remembered as the precursor and the pathfinder of successful flying-machines.”

In honor of Langley’s contributions to the science of aerodromics, the Smithsonian Board of Regents established the Langley Gold Medal in 1908. Award recipients have included Orville and Wilbur Wright, Charles Lindbergh, Alan Sheppard, Wernher Von Braun, and Neil Armstrong. In 1917, the National Advisory Council for Aeronautics (NASA), the U.S. Army and Navy opened a joint aircraft proving ground in Hampton, Virginia designated as “Langley Field,” which would become “Langley Air Force Base” in 1948. In 1920, the U.S. Navy converted the cargo ship USS Jupiter into the Navy’s first aircraft carrier, the USS Langley.

“Langley Aerodromes on Exhibit,” Smithsonian Institution Archives, Record Unit 95, Box 15, Folder: 9-B, https://ids.si.edu/ids/deliveryService?id=SIA-2002-12149

Samuel Pierpont Langley. Photo courtesy of the Smithsonian Institute.