A Curious Mind

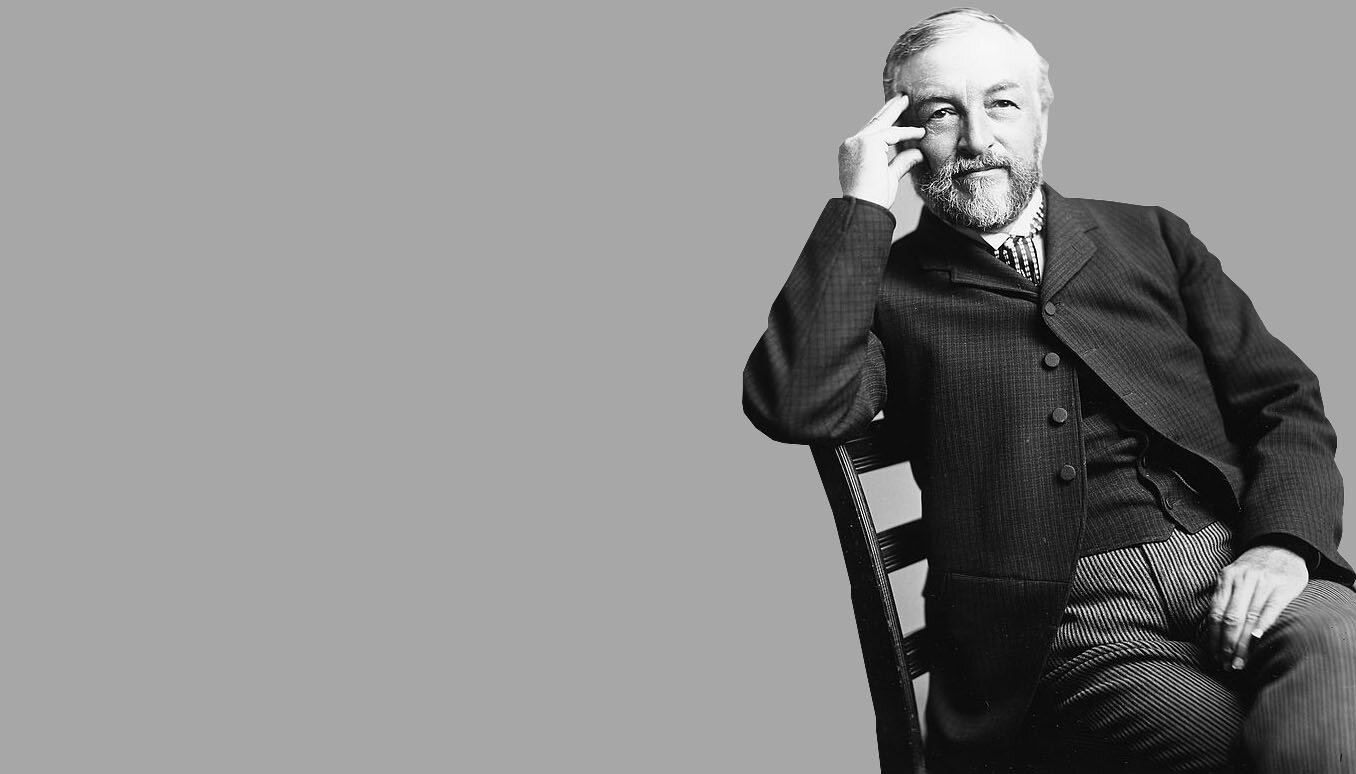

Born on August 22, 1834, Samuel Pierpont Langley spent his formative years in Roxbury, a neighborhood of Boston, Massachusetts where his father was a wholesale merchant. Langley, who later recounted, “I cannot remember when I was not interested in astronomy,” began observing stars through his father’s telescope by age nine. At age eleven, Langley enrolled in the Boston Latin School, the oldest public school in the United States, which fostered his early interest in all things mathematical and mechanical. After graduating in 1851 at age seventeen, Langley realized that employment opportunities in astronomy were limited and decided to focus on civil engineering and architecture. Rather than attend college, Langley found employment with a Boston architecture firm. At the same time, Langley satisfied his love of astronomy by building telescopes with his brother and studying the planets, moon, and stars. He would eventually continue his architectural career in St. Louis and Chicago, where he became proficient in mechanical and freehand drawing.

In 1864, Langley returned to Boston and in 1865 embarked on a Grand Tour of Europe with his brother to study at museums and learn about new scientific discoveries and innovations. Upon his return, Langley would finally find employment in the field of astronomy at the Harvard College Observatory where he served as an assistant, maintaining and building the facility’s equipment. In 1866 he moved on to serve as a Professor of Mathematics at the U.S. Naval Academy where he was also in charge of restoring the observatory.

In 1867, Langley accepted the position Professor of Astronomy and Physics and Observatory Director at the Western University of Pennsylvania’s (now University of Pittsburgh) Allegheny Observatory. The observatory had fallen on hard times and possessed inadequate equipment and funding to advance astronomical studies. In 1869, Langley devised a plan to generate funds needed to modernize the observatory.

Post-Civil War Pennsylvania experienced rapid expansion of the railroad system which carried coal and iron ore to factories along the East Coast. The synchronization of time between stations was critical to maintaining the flow of goods and passengers and to avoid accidents. With a seemingly infinite number of railway stops along each line, time management had become a significant limitation on the railroad’s capacity. Langley realized that astronomy held the key to solving this challenge. Utilizing a transit telescope at the Allegheny Observatory, Langley used regular celestial observations to create the Allegheny Time System, a highly accurate time clock with readings transmitted twice daily to over 300 Pennsylvania Railroad telegraph offices over 2,500 miles of track. The railroad agreed to pay the observatory for this service, and soon jewelers, watchmakers, banks, and government offices followed suit. The revenue stream allowed Langley to greatly improve the observatory and expand the scope of his astronomical research.

Allegheny Observatory, c. 1886, by George W. Tea. (Courtesy of Archives Services Center/University of Pittsburgh)

Studying the Sun

With new equipment at the Allegheny Observatory, Langley turned his attention to studying the sun, one of the few heavenly bodies he could view in detail through the smoke-filled atmosphere in the Pittsburgh area. In the late 1860’s, scientists knew little about cosmic radiation and the impact of solar wind and storms on Earth. Viewing the sun’s corona, or outer atmosphere, where these phenomena originated, was obscured by the brightness of the sun itself. Langley began a series of expeditions to study the sun during solar eclipses, when the moon blocked the sun’s intensity long enough for him to observe the corona. It was during these observations that Langley’s keen eye and technical drawing skills set him apart from other researchers of his day. Long before telescopic cameras were able to capture images of the sun’s surface, Langley’s drawings would help launch the “new astronomy,” concerned with the physical nature celestial bodies, and the application of physics to the interpretation of astronomical observations. This new science would become astrophysics.

Samuel Pierpont Langley’s drawing of a sun spot, 1873.

In the mid-1600’s, Sir Isaac Newton utilized a prism to prove that sunlight wasn’t a single color but a spectrum of colors, each with its own wavelength. By the early 1800s, Sir William Herschel had discovered that the different parts of this spectrum, possessed different temperatures. More remarkably, temperature variations continued beyond the visible light spectrum, meaning that solar radiation existed beyond what the human eye could see.

Again relying on skills honed in his youth, in 1879 Langley began building a device that could measure minute changes in temperature across the solar spectrum. In 1880, he unveiled his invention, the bolometer, which was shown to be a thousand times more sensitive to radiant heat than prior temperature measuring devices. In 1881, Langley and a team of scientists would climb the 14,495 summit of Mount Whitney, California and use his bolometer to reveal unknown regions of the invisible, infrared spectrum. In 1909 the Smithsonian constructed a shelter for astronomical observers on Mount Whitney, which Langley deemed “the best location in the country for meteorological and atmospheric observations.” A nearby mountain, Mount Langley, was officially named for Samuel in 1943.

Photo of Observatory Shelter, Mount Whitney, 1909, Smithsonian Secretary’s Report for 1909.

In 1886, Langley was awarded the National Academy of Science’s first Henry Draper medal for investigations in astronomical physics. His research and the bolometer were utilized by Svante Arrhenius to discover the greenhouse effect in 1896. In 1898, Langley received the French astronomical society’s highest award, the Prix Jules Janssen.

For More on Langley’s work at the Allegheny Observatory, check out:

Undaunted, the Forgotten Giants of the Allegheny Observatory (2012)

A documentary by Dan Handley Science Media.

The surprising story of how the Allegheny Observatory has been a world leader in the study of the stars since the 1860s. Self-educated, and often facing unrelenting hardships, the people associated with the Allegheny Observatory defied the odds to make enormous contributions to the founding of astrophysics and early aviation.

Click below to watch for free on Filmzie:

Aviation Pioneer

In 1887 Langley was named assistant secretary of the Smithsonian Institution. The position was short-lived. Langley was elevated to the Director of the Smithsonian Institute (the 3rd director since its founding in 1846) when the Director died less than a year later. Inspired by a lecture on the work of an amateur aviation experimenter, Langley asked himself, “whether the problem of artificial flight was as hopeless and absurd as it was then thought to be. Nature had solved it, and why not man?”

From 1887 until 1903, Langley’s invested his energy and significant Smithsonian resources in the pursuit of mechanical flight. He constructed an immense flight testing machine, called a “whirling table,” consisting of belt-driven 30’ spinning radial arms, eight feet off the ground, which enabled him to study lift, center of gravity, and balance characteristics of over 100 different model prototypes.

By incrementally adjusting wing placement and attitude, Langley derived mathematical equations for the power (thrust) and properties of rigid plane surfaces needed to achieve and sustain flight. Over the next four years, Langley’s models grew larger, up to 4-1/2’ long with 4’ wingspans, and more complex, with design characteristics that would be incorporated into aircraft for decades.

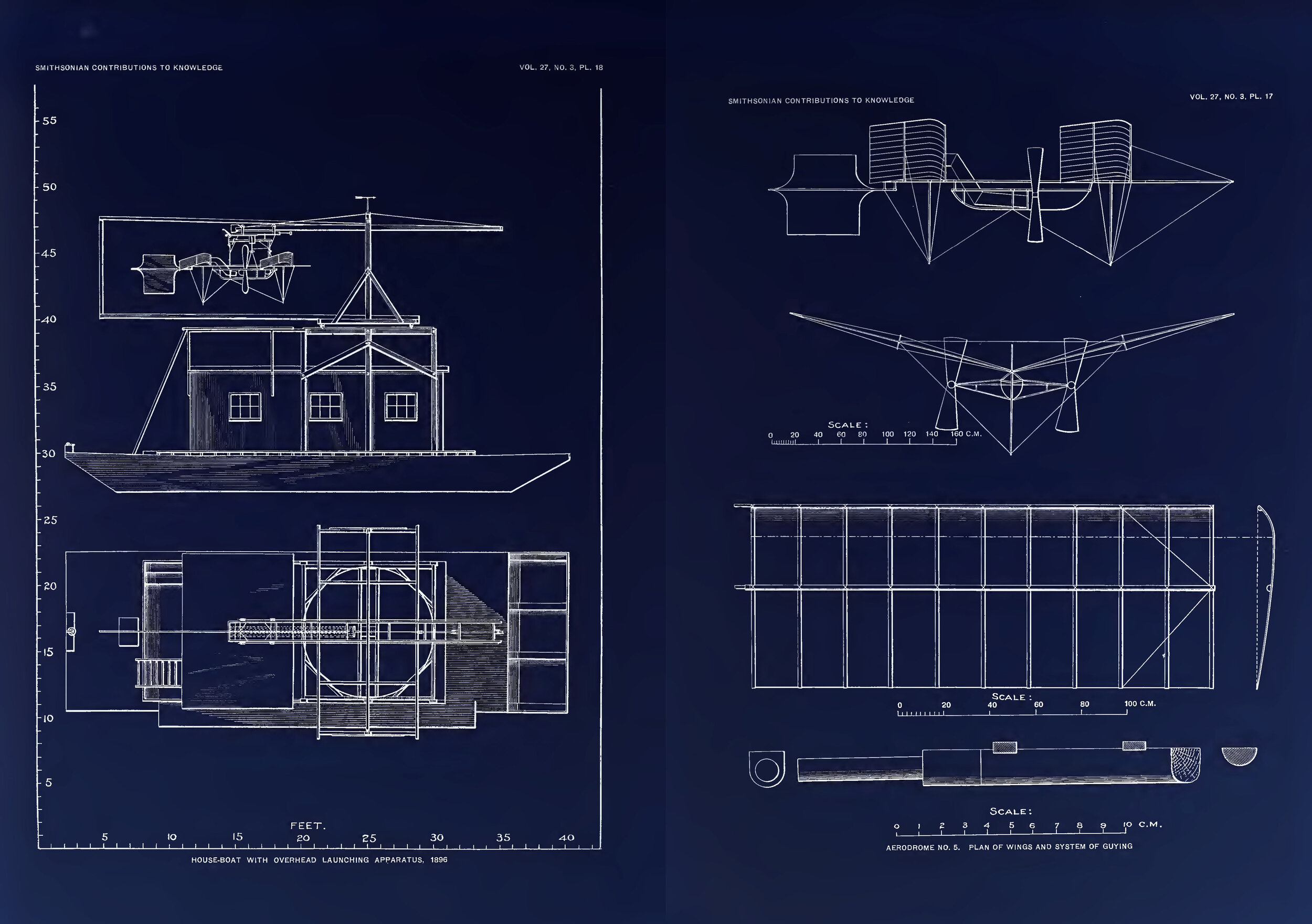

In August 1891, Langley published the results of his work in “Experiments in Aerodynamics,” a report of the Smithsonian Contribution to Knowledge. In his introduction, Langley stated, “I do not undertake to explain any art of mechanical flight, but to demonstrate experimentally certain propositions in aerodynamics which prove that such flight under proper direction is practicable.” Over the next five years Langley continued to pursue mechanical flight with the construction and testing of larger, unmanned “Aerodromes” (Greek for “air runners”).

Langley’s greatest success came in 1896 with the first successful heavier-than-air mechanical aircraft flight in human history. On May 6, the 14’ long Aerodrome No. 5 was launched from atop a houseboat in the Potomac River in Stafford County, Virginia and flew approximately 3,300 feet in 90 seconds before gently coming to rest in the water. On November 28, 1896, Langley launched Aerodrome No. 6 from the same location for a flight totaling 4,200 feet at an average speed of 30 miles per hour.

Disappointment & Posthumous Recognition

In 1898, Langley received a $50,000 grant from the Board of Ordnance and Fortification to construct a man-carrying aerodrome motivated by President McKinley’s interest in its development as a weapon of war. After successful launches of quarter-size models in 1898 and 1899, Langley constructed the full-size “Aerodrome A” which was readied for test flight in October 1903. With his assistant Charles Manley at the controls, the aerodrome crashed into the Potomac immediately after launch and Manley barely escaped with his life. A conflict with the launching mechanism was blamed for the failure and the aerodrome was prepared for a second attempt in December. Again, the craft crashed and further flight attempts were cancelled. On December 17, 1903, the Wright Flyer successfully took to the sky in Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, becoming the first powered, aircraft to achieve controlled, sustained flight with a pilot aboard.

The failure of his aerodrome despite the massive expenditure of public funds in support of the effort led to ridicule and great embarrassment for Langley, whose despair amplified upon the discovery that the Smithsonian’s accountant was embezzling funds in 1905. Shortly thereafter Langley suffered a stroke and died on February 27, 1906 at the age of 71.

In December, 1906, Langley was remembered by fellow aviation pioneer Octave Chanute, ”He rescued the problem from contempt, he laid the lines which must be followed, and, having published the results of his experiments and given other men data upon which to conquer the air, he will ever be remembered as the precursor and the pathfinder of successful flying-machines.“

In honor of his contributions to the science of aerodromics, the Smithsonian Board of Regents established the Langley Gold Medal in 1908. Award recipients include Orville and Wilbur Wright, Charles Lindbergh, Alan Sheppard, Wernher Von Braun, and Neil Armstrong. In 1917, the National Advisory Council for Aeronautics (NASA), the U.S. Army and Navy opened a joint aircraft proving ground in Hampton, Virginia designated as “Langley Field,” which would become “Langley Air Force Base” in 1948. In 1920, the U.S. Navy converted the cargo ship USS Jupiter into the Navy’s first aircraft carrier, the USS Langley.