The “Air-Runners”

Building on his “Experiments in Aerodynamics,” Samuel Pierpont Langley pivoted to the study of “Aerodromics,” the science of powered flight.

The greatest challenge Langley had to overcome was one that had plagued all of man’s prior attempts at mechanical flight, to create a machine that was light enough to fly while powerful and strong enough to carry the engine and fuel needed to sustain flight. In the early 1890’s the standard gas-powered combustion engine weighed approximately 500 pounds. Based on his aerodynamic studies, Langley’s engine needed to produce 1 hp of power and weigh no more than 3 pounds. Such an engine didn’t exist. Langley and his team would have to invent it.

He experimented with different motors that used compressed air, electric batteries, steam, and carbonic acid to determine the lightest alternative and ultimately settled on the steam engine, which was in common use in locomotives and ships, but was heavy and required both fuel and water to operate. The engine needed to produce steam quickly and at high pressure to maintain constant propeller motion. By 1893 the team had settled on a “beehive” boiler utilizing copper coils paired with an aeolipile, which consisting of a compressed air chamber, a reservoir fuel tank, a gas generator where liquid gas converted to gas and burners that ignited the gas to heat the boiler. The assembly thus converted the steam to rotational energy to turn the aerodrome’s propellers.

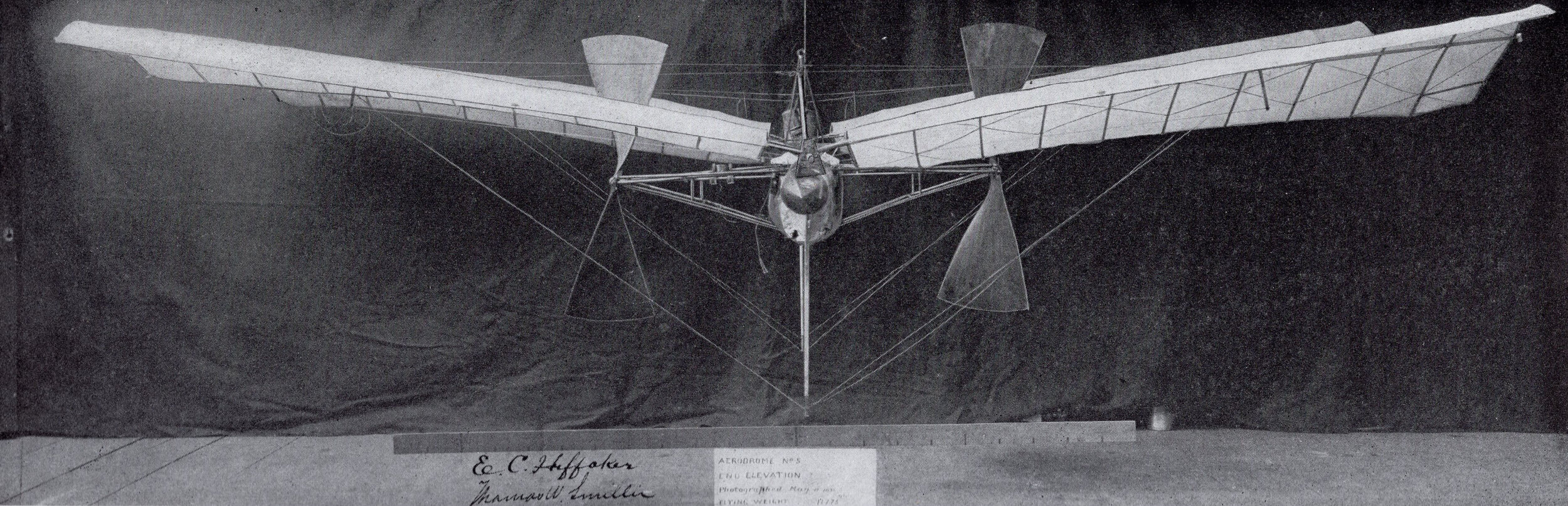

Multiple refinements to the aerodrome’s propulsion system through 1894 enabled Langley to achieve an output of 1.1 horsepower at a total weight of 6.4 lbs, which was still too heavy to be carried by his existing aerodrome frames. New aerodromes (#4 & #5) were devised with reinforced steel frames, and stronger, yet lighter wings. To reduce wing deformation, Langley attached vertical guy posts directly to the steel frame and strung piano wire between the posts and wing ribs for stability. Aerodrome #4 proved to be structurally weaker than Aerodrome #5 and was modified so extensively it was given the new name, Aerodrome #6.

“Aerodrome in Work Area,” Smithsonian Institution Archives, Record Unit 95, Box 52, Folder: 2, https://ids.si.edu/ids/deliveryService?id=SIA-2002-12149

As early as 1892, Langley understood that mechanical flight wasn’t possible without an effective system for launching his aerodromes into the air. Early failed attempts included dropping the aircraft from a height of 25’ in hopes that the propellers could produce sufficient thrust to maintain flight. They could not. Eventually the team settled on a spring-actuated catapult system with supporting a carriage on rails that would provide a straight “cast off” of sufficient velocity while minimize damage to the aerodrome’s frame during launch. The web of piano wire guys installed to provide wing stability from below the aerodrome required that it be secured to the carriage from above.

Langley’s aerodromes had no landing gear, nor means for flight control other than wing positioning and tail adjustments before and after each flight. In order to get multiple test flights out of each aerodrome with minimal damage, the team decided that the tests should be performed over water and built a specially designed houseboat with their catapult installed on its roof, in essence, the world’s first aircraft carrier. The lower portion of the 30’ x 12’ boat included sleeping quarters and space for storage and repairs.

Langley’s team searched for the ideal location for their flight testing and chose “Chopawamsic Island,” a small island at the confluence of the Potomac River and Chopawamsic Creek in Stafford County, Virginia not far from the Quantico railroad station. The Washington and Richmond Railroad line ran directly between Washington, DC and Quantico, providing easy access for Langley and his team and transportation of the aerodromes. The island also provided overnight accommodations as it had been used as a duck hunting club for the Mount Vernon Ducking Society. The houseboat allowed the launching platform to be steered so that launches could be made into the wind, despite changing wind directions. The houseboat was towed to the west side of Chopawamsic Island in May, 1893 where the waters were calm and shallow, so shallow in fact that the area was partly dry during low tide. From this location the team conducted a series of launches of dummy aircraft throughout 1893 and 1894 to test and make adjustments to the launching mechanism.

“Houseboat with Overhead Launching Apparatus, 1896,” Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge Vol 27, No. 3 Pl. 18, Langley, S. P., and Charles M. Manly. Langley Memoir on Mechanical Flight. Published by the Smithsonian Institution, 1911.

Throughout 1894 and 1895 a series of failed flight tests led to additional modifications to both Aerodrome No. 5 and No. 6, to include tandem wings constructed of lightweight wooden ribs covered in silk to achieve longitudinal stability. The single-cylinder gasoline engine and flashtube boiler were further refined to turn the twin 38” propellers 500 revolutions per minute. Finally, modifications to the launching mechanism were completed to avoid frame and guy wire entanglements that had doomed previous test flights.

By May 1896, the assembled aerodromes had wingspans of 13 feet 8 inches, measured 13 feet 2 inches long, and weighed approximately 24.3 lbs, which included 2 lbs of gasoline and water, enough to power the engine for 2 minutes.

“Side and End Elevations of Aerodrome No. 5 May 11, 1896,” “Aerodrome No. 5. Plan View. October 24, 1896,” Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge Vol 27, No. 3 Pl. 27A & 27B, Langley, S. P., and Charles M. Manly. Langley Memoir on Mechanical Flight. Published by the Smithsonian Institution, 1911.

On May 4, 1896, the project mechanics, Mr. Reed and Mr. Maltby, brought Aerodromes No. 5 and 6 to Chopawamsic Island in advance of Langley, and his guest, Alexander Graham Bell, who would arrive the following morning. After years of agonizing trial and error, its unlikely that any member of the party went to sleep on May 5th expecting the remarkable success they’d witness the following afternoon.